Introduction to GPS

Peeking under the hood of satellite navigation

Introduction

GPS is one of those things that everyone uses all the time but nobody really thinks about.

A recent conversation I had with friends turned up some surprising questions. GPS communication is two-way, right? That’s why it doesn’t work in cities, because too many people are trying to use it? Don’t they have to keep adding satellites as more people use the system?

It turns out these are all common misconceptions. The genius of GPS, and the reason it is so ubiquitous, is that communication is one-way. Your device doesn’t have to transmit anything to work out its location, so there is no limit to the number of users and the US government has no way of knowing when you use it.

Most people have a basic mental model for how GPS works that goes something like, “My phone finds the distance to three satellites and uses that information to triangulate its position.” That covers the basics, but it turns out there are some interesting nuances to this process.

This post aims to lay out the fundamentals of satellite navigation in an easily digestible fashion.

Background

First, a few definitions. GPS stands for Global Positioning System, which was developed by the US Air Force and first became operational in 1993. Russia has its own system, called GLONASS (Global Navigation Satellite System), which has been operational since 1995. China and the EU also recently completed constellations called BeiDou and Galileo, respectively, and Japan and India have systems which do not (yet) provide global coverage.

The generic term for these systems is GNSS, which stands for Global Navigation Satellite System. Most modern receivers support both GPS and GLONASS, and Galileo and BeiDou have been adopted rapidly in consumer devices over the past few years. To reflect this development the remainder of this post will refer to GNSS generally rather than the US-specific GPS.

Fundamentals

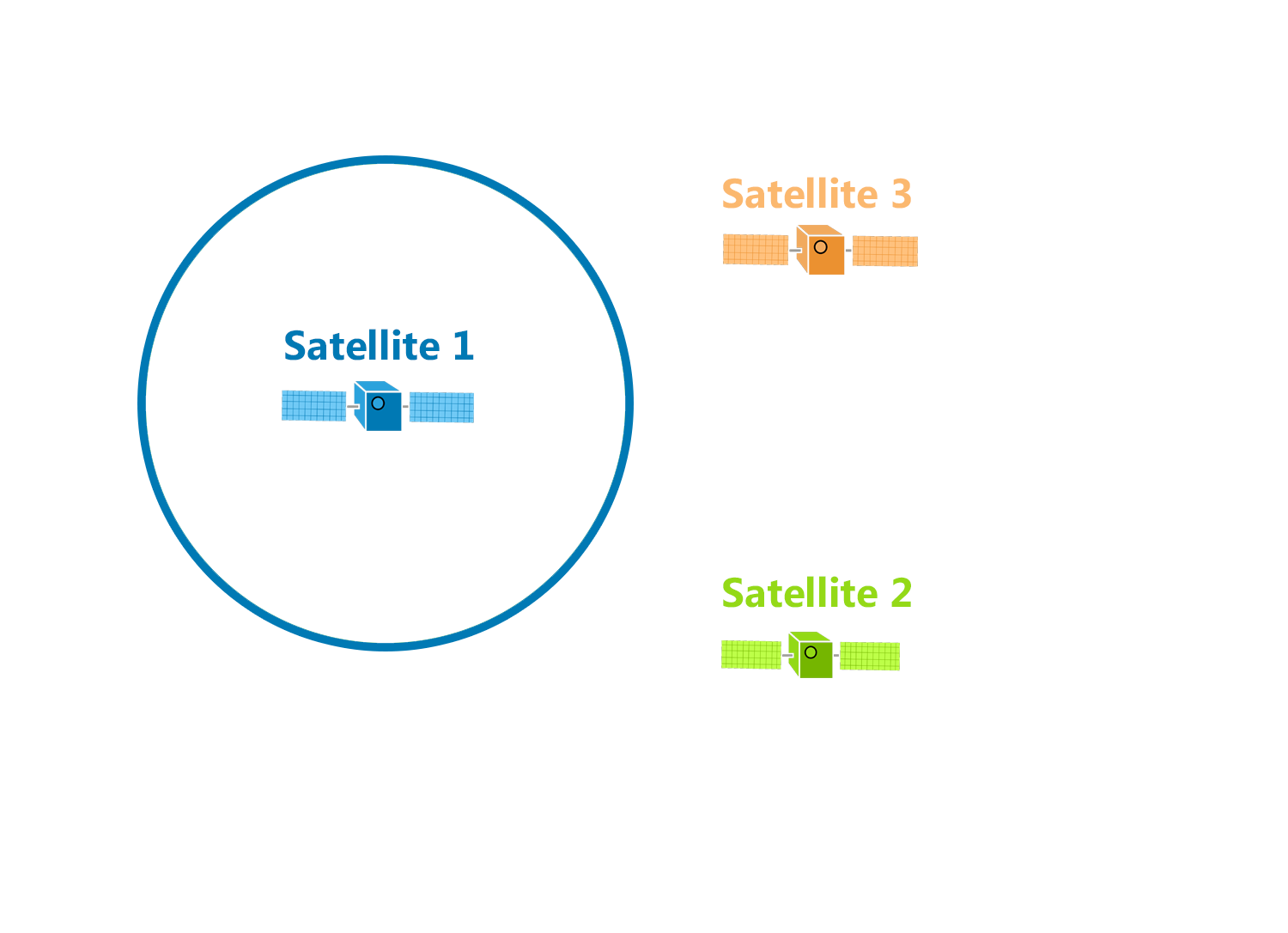

So, how do these systems triangulate your position from satellite signals? Let’s start with that mental model of triangulation that I mentioned earlier. The basic concept works like this: if you know the range $r_a$ between a point on a plane and a known location $A$, you know that the unknown point must be located somewhere on the circle with radius $r_a$ centered on $A$.

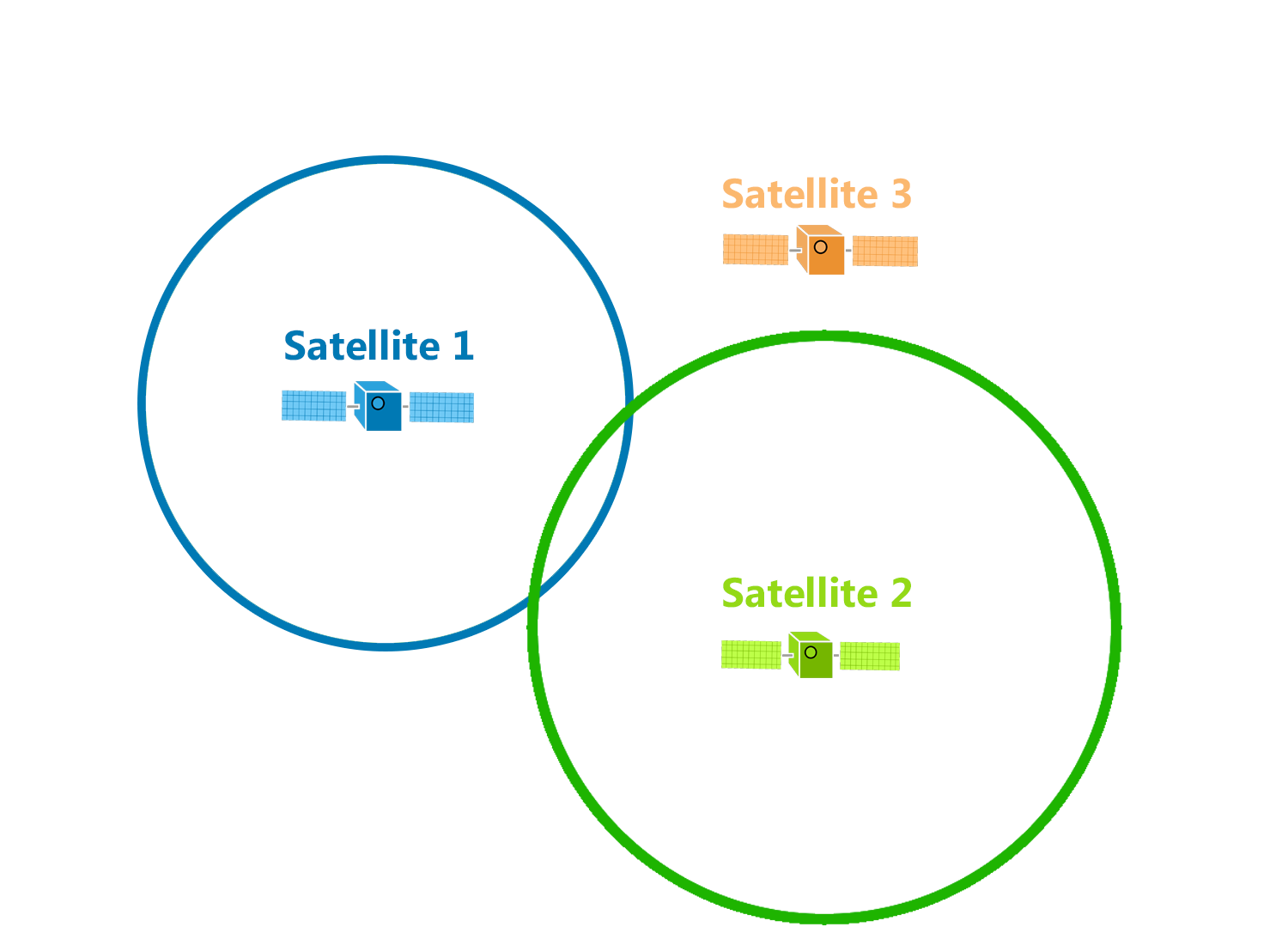

If you know the range $r_b$ to a second point $B$, then your mystery point is at one of two intersections of the circles centered at the known points.

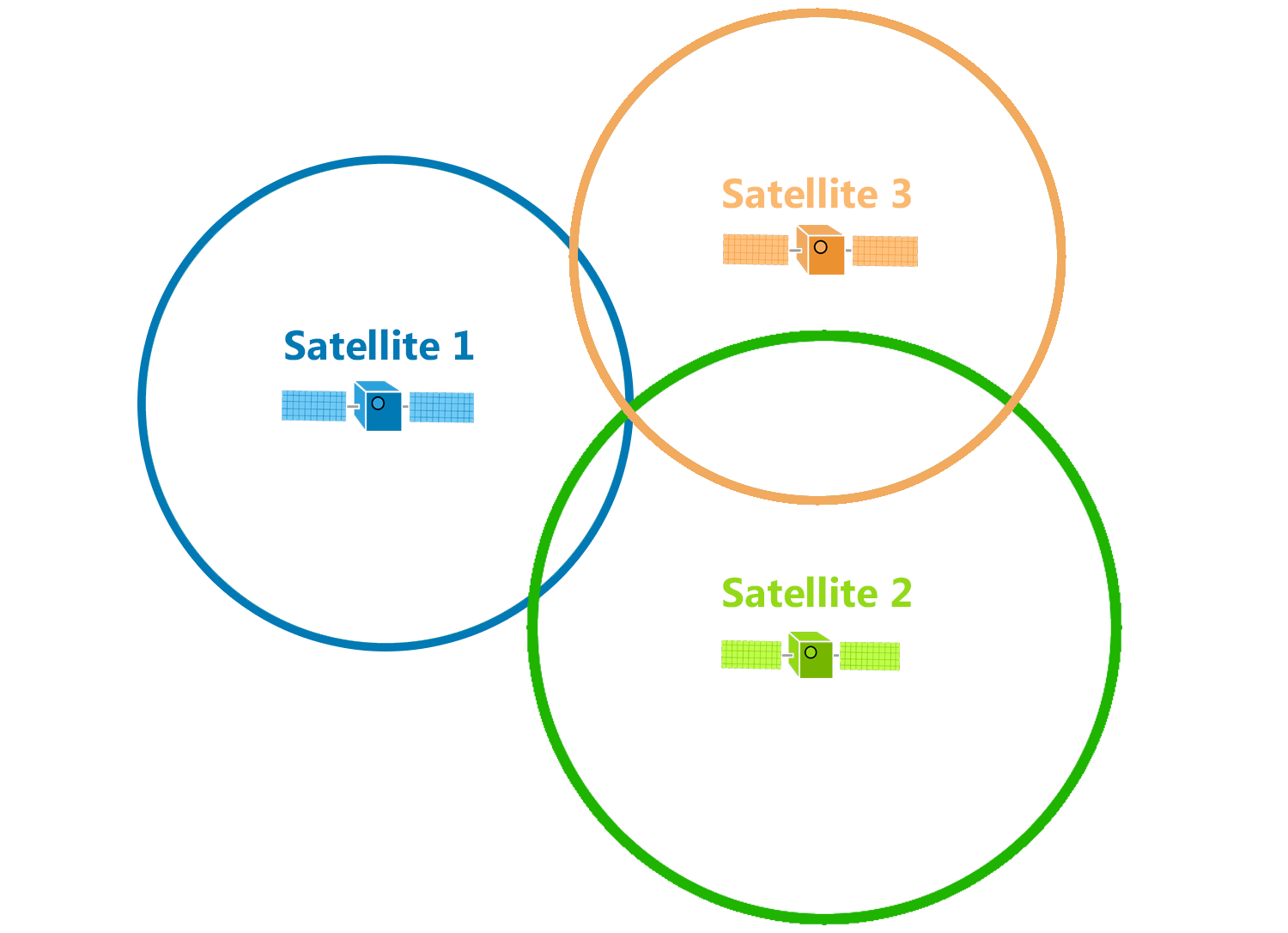

Add a third reference point and boom, you’ve located your mystery point.

This mental model assumes several things:

- We know the locations of at least three reference points

- We can easily find the range to those reference points

- Our world is two-dimensional

Unfortunately none of these assumptions hold in satellite navigation. Let’s examine how GNSS constellations address each of them in turn.

Reference Locations

Our reference points for triangulation are satellites, which orbit the Earth at approximately 3.9 km/s.1 Thus we cannot assume our reference points are fixed, and we must determine their positions every time we want to triangulate our location.

Predicting a satellite’s exact orbit is difficult due to variations in the Earth’s gravitational field, disturbances from the sun and moon, and many other factors. These disturbances cause the satellite’s orbit to drift over time. Ground stations on Earth track their signals, calculating new orbital parameters for each satellite every two hours and uploading them for broadcast.

GNSS constellations do not have enough transmission bandwidth to broadcast their exact position to the necessary level of precision every second. Instead the satellites broadcast their orbital parameters every few minutes. Receivers decode these signals and save the parameters, using them to calculate the satellite’s position whenever it is needed.

The details of GPS signal transmission are well beyond the scope of this post, but there are several fascinating signal processing techniques involved. Check out Andrew Holme’s Homemade GPS Receiver project if you are interested in learning more.

Range Finding

So, we know where the satellites are. How do we figure out the range from each one to the receiver?

Most rangefinders (e.g. sonar, radar, lidar) operate on a time-of-flight principle: send out some sort of pulse and measure how long it takes to come back. But sending pulses consumes energy - energy which is likely in short supply for a mobile, battery-powered receiver. Two-way communication would also require coordination with the satellites, constraining system capacity to the number of simultaneous connections the satellites can maintain.

To reduce receiver complexity and eliminate constraints on receiver count, GNSS constellations are designed for one-way communication between satellite and receiver. That means the satellite transmits the signal and encodes the time of transmission, allowing the receiver to simply measure time of reception using its own clock and subtract transmission time to get time-of-flight.

There’s only one problem. Radio waves travel at the speed of light, which is over 299,793 km/s. At such high speeds, very small errors in the time-of-flight measurement can result in huge changes in the estimated position. GNSS satellites carry multiple atomic clocks, which use cesium or rubidium oscillators, to ensure that signal transmission time is measured accurately. Commodity GNSS receivers use quartz clocks, which are cheap and energy-efficient, but cannot keep time accurately enough to provide a dependable measurement of the signal reception time.

Receivers get around this issue by obtaining an extra measurement from an additional satellite. The additional measurement provides another independent variable, enabling the receiver to calculate the offset between its clock and the GNSS reference clock as well as its position in three dimensions.

This process makes GNSS constellations the most accurate and widely available time server in the world. You can synchronize your clock to within 100 nanoseconds2 of UTC anywhere with GNSS coverage, which means, well, anywhere on Earth. GPS time is used for time synchronization by civilian and military aircraft, financial systems, critical infrastructure, networking equipment, and many other industries. In fact, time synchronization is so central to satellite navigation infrastructure that GPS’s governing bodies go by the acronym PNT, which stands for Positioning, Navigation and Timing.

Three-Dimensional Triangulation

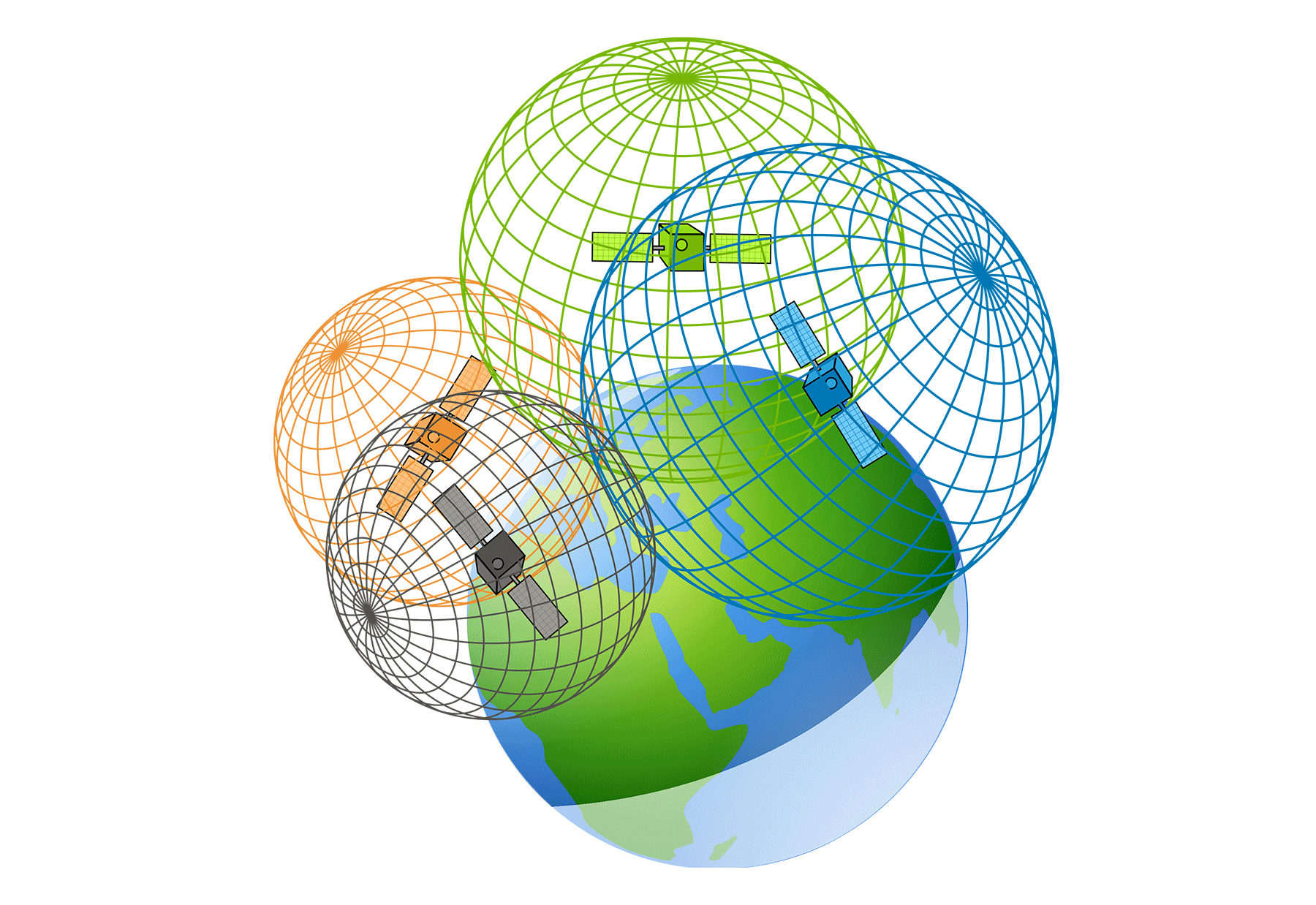

The world is not flat, so a GNSS receiver cannot assume its location lies on a plane. To address this, let’s generalize the concept of triangulation to three dimensions. The range to a single known reference point narrows our location down to a sphere of points located $r_a$ from the reference. A second reference narrows the possibilities down to the circle where the two equidistant spheres intersect. A third reference reduces the options to two points.

You can probably guess where this is going. Adding a fourth reference does indeed resolve the ambiguity and allow us to triangulate our mystery point.

In the case of satellite navigation, this fourth reference can actually be Earth. How? In the three-satellite case, one of the two candidate locations will be out in space, farther from Earth than the satellites themselves.

In most cases we can eliminate that candidate and call it a day. However, because your GNSS receiver needs to solve for time as discussed above, a full position solution still generally requires measurements from four satellites.

Conclusion

Hopefully you know have a solid conceptual understanding of what happens inside your phone when you click that little crosshairs button on Google Maps. Check out my next post for a detailed tutorial explaining how to calculate your position from raw GNSS receiver data.

Note: figures in this post are from gisgeography.com.

-

GPS Space Segment, Navipedia ↩